Eight years ago I received a text from an old friend, a former doorman in Boston. “Did you hear about Jack? Heart failure. Does not sound good.”

During the spring of 1990, I was struggling. I was essentially broke, without a car, close to being homeless, and increasingly hopeless about my future. Bouncing around with little direction, I was still basically a kid with a few random credits from Bridgewater State College and even fewer from Northeastern University. I was living out of a gym bag and carrying a guitar. It had been suggested by a friend who had allowed me to stay at her apartment in Brighton just off the Boston College campus that it would be advisable for me to remain in the city. I had become acclimated to living in Boston. My grandmother, who lived in Boston most of her life, would often tell me that the city gets into your blood, words that I think in retrospect she meant more as an observational prediction than an attempt to make conversation.

By the time I applied for a job at the Boston Marriott Copley Place Hotel for the second time in nine months, employment was essential. I had already interviewed there earlier that fall for a job as a bellman, but had been rejected despite the fact that I had a few years of experience doing the same work at a smaller hotel just south of the city. For the sake of the opportunity, I pretended that I was interested in an available position at the hotel’s front desk. During my interview, the front desk manager mentioned that she thought I might actually be a better fit at the bellstand. Although I was in full agreement, my immediate inclination was to get up and run from the hotel thinking I was about to repeat what had already been an awkward meeting with the same guy who had turned me down only a few months before. As luck would have it, a new Bell Captain had taken over at the Marriott. My introduction to Jack Prihoda completely altered the trajectory of my life. In his typically understated way, it was Jack who recognized and acted on a potential in me that even I was unable to see for myself at the time.

It was impossible to tell all those years ago that the humble U.S. Coast Guard veteran who would careen his 1983 Toyota station wagon along the Jamaicaway en route to Boston’s Copley Square every morning would become such a pivotal figure in so many lives. He didn’t attempt to manage with any prescribed manner. Jack had a way of accentuating the best in everyone and provided opportunity to those that he thought needed it the most. His sometimes gruff intensity about the job was almost always overshadowed by his predictable sense of humor. As a result, it was nearly impossible not to work hard for Jack. With an almost fatherlike influence on anyone who was fortunate enough to work for him, Jack was effective managerially for the same reasons that he was effective personally, you knew that he had your back and it was clear that he cared about people. He would always find time regardless of who you were or what it was that you needed. Jack was able to make authentic connections with anyone, not because he considered them to be of some benefit to him, but because he had a curious place in his heart for people and their interests.

Like a positively motivated Fagin from the Charles Dickens novel, Oliver Twist, Jack became the ringleader of a band of young men and women whose potential he identified and took into the fold. This included sculptors, lawyers, inventors, doctors, actors, servicemen, stand-up comedians, photographers, and musicians just to name a few. Jack’s crew at the hotel consisted of men and women from all over the world and every walk of life. Many would eventually move on with Jack’s encouragement, while others continued working at the hotel. But returning to Jack at the bellstand at any point was always like coming home. Jack modestly developed lasting friendships with interesting people such as former United States Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, Baltimore Orioles Scout Deacon Jones, and former Kansas City Royals second baseman Frank White. He often showed up at work with ridiculous stories about mishaps that occured on his way to the hotel in the early morning including attempts to fish in various Boston ponds along the way only to be pursued by city officials demanding a permit, or car trouble leading to his favorite mechanic who would open his hood and continuously exclaim, “Holy smokes!”

Almost everyone on Prihoda’s staff was referred to by a nickname. Mine was Joke Boy, a name I earned after I switched Jack’s size 44 uniform with a size 38 late one night while passing through Copley Square, then keeping a surprisingly straight face the next morning as he attempted to squeeze into a much smaller uniform for his early morning shift. After uttering a few choice words, I could hear Jack’s reaction behind me as I quickly made my way out to the hotel lobby, “Joke Boy! I’m gonna’ whack you!” The name stuck, as did many of the others such as Milhous, Curtain Rod, Freelance, Trouble Maker, Shis Boom, Lurch, Squash Melon, Ningles, Corn Flake, Big Man, Movado, Porcelana, and Flat Tire. When I decided to start back at Northeastern during the fall of 1991, Jack was more than supportive. He had also gone to Northeastern and always took a specific interest in the various classes that I ended up taking along the way. He often referenced his time spent in Vietnam serving as the baker on the Coast Guard cutter Chase where he would purposely get under the skin of his commanding officer making loaves of bread in the shape of whales. Regardless of the circumstance, Jack had a way of putting people at ease and was always capable of bringing levity to any situation.

During the fall of 2016 almost two decades after leaving the Marriott, I chanced upon a 1970s style Philadelphia Phillies uniform jersey for cheap money in a second-hand store and mailed it anonymously to Jack at the hotel, adding only the name Bake McBride as the return address. Jack was originally from Trenton, New Jersey, and a huge fan of all nearby Philadelphia sports teams. This particular jersey had the number 22 on the back, the number initially worn by Phillies outfielder Bake McBride during the 1970s. There was absolutely no hint that the package had come from me, but several months later when I put a call through to Jack at the Marriott he answered the phone in true Jack Prihoda fashion without hesitation saying, “Who’s this? Bake McBride?”

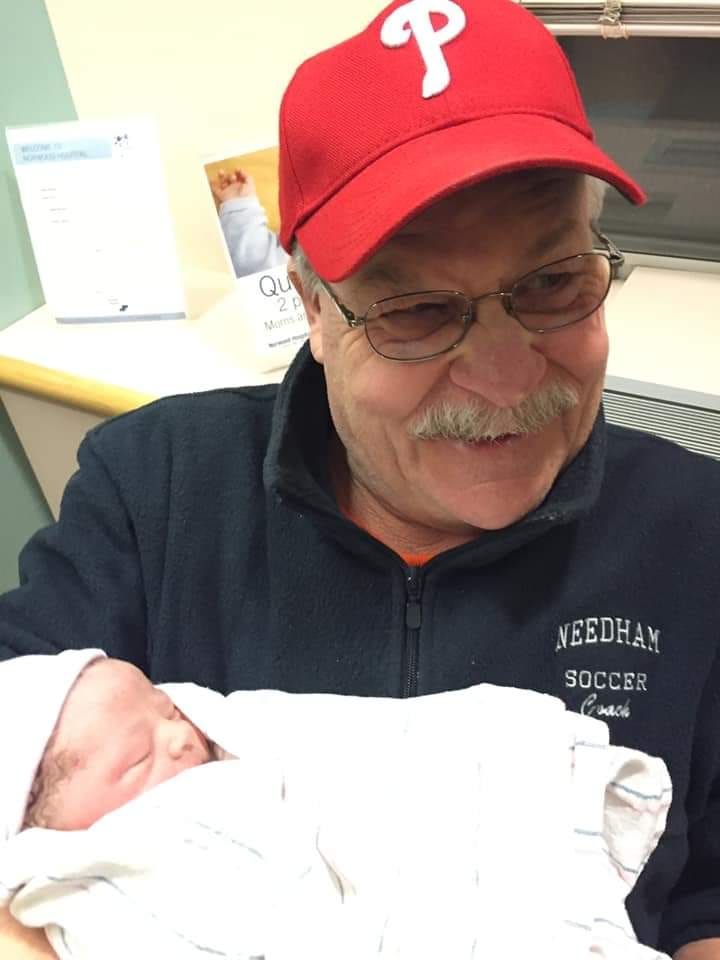

Jack was a man who brought people together. When we lost Jack eight years ago, his passing led to what was truly a celebration of his life, his family coming together with Marriott staff members past and present. Jack was a devoted family man who celebrated 43 years of marriage to his wife, Audrey, and could not have been more proud of his two daughters, Sarah and Tracy. At the time, he had fallen into a new role as Opa to his new grandchildren, Kyra and Jack. His oldest daughter, Sarah, delivered an emotional and courageous speech with her sister Tracy by her side. When it came time to share stories, it was his bellmen that took the floor one after the other, all adopting mannerisms and characteristics inspired by Jack echoing the same common sentiment: I don’t know where I would be today if it had not been for Jack.

Being together as a group again eight years ago felt a bit like old times, sharing stories, poking fun at each other, all while offering support to Jack’s family in the same way that Jack would have, with compassion, caring, and laughter. In many ways, we were like a family at the hotel due in part to Jack’s style of leadership, but more likely due to his sense of humanity. The camaraderie that we developed at the hotel has had lasting influence, maybe in a way that is similar to how Jack looked back on his days on the Chase. And if there is no better tribute to Jack’s unmistakable influence, I feel like he’s always there with me any time I find myself at an impasse, the memory of Jack helping me turn what appears to be a difficult situation into one that usually ends with laughter.

Sometimes when I’m staying in Boston I’ll take an early morning walk up Columbus Ave., grab a coffee at Flour off of Clarendon Street, and make my way through Back Bay Station into Copley Square like I did almost every day at the break of dawn decades ago. But it still seems impossible for me to enter Copley Square in the calm early morning without seeing Jack Prihoda ambling into the Boston Marriott Copley Place dressed in t-shirt and jeans whistling to himself on his way to work.

In Jack Prihoda’s case, greatness was masked in the most common attire.

If you like my articles, please hit the “LIKE” button. It will help to let me know that you are enjoying my writing.

I welcome and invite you to COMMENT.

And please SHARE these posts! This gives added support to my Substack page and also helps to add new readers.

Thanks so much to anyone who is reading Journeys with Jay!

What a wonderful story, Jack sounds like an amazing man, great story. I know is daughters Sarah and grandkids wonderful family.

Thank you for sharing your memories of Jack. I learned more about the man that I only knew for the final 10 years of his life. I’m confident his family cherishes these memories as well.