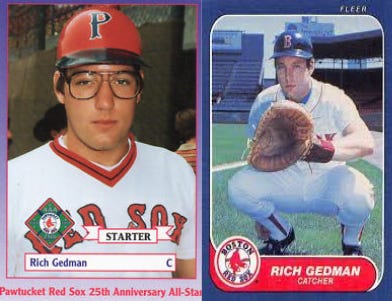

CATCHING UP WITH FORMER RED SOX CATCHER RICH GEDMAN

He was the local kid from Worcester, the one who got called up on the heels of Carlton Fisk’s unpopular exit to the Chicago White Sox. A left-handed hitting catcher who had displayed some offensive power during his stops in the minor leagues, Gedman initially paled in comparison to the right-handed hitting Fisk, the Red Sox legend who customarily used Fenway Park’s left field wall to his powerful advantage.

During his first extended call-up, Gedman hit .288 with 5 home runs and knocked in 26 runs during the strike-shortened season of 1981. His numbers were enough to finish second in American League Rookie of the Year voting behind left-handed pitcher Dave Righetti of the New York Yankees. Whatever potential power the Red Sox had projected in Gedman’s bat, however, had all but evaporated by 1983. Showing the hard-nosed determination that became a trademark of the developing catcher, Gedman continued to work hard transforming his approach at the plate with hitting coach Walt Hriniak and finally emerged in 1984 hitting .269 with 24 homers and 72 RBIs. In 1985 he raised his average to .295, smacked a respectable 18 homers and drove in 80 runs. By 1986, Gedman had established himself with the Red Sox helping to cultivate young Sox pitching talent along the way like John Tudor, Bobby Ojeda, Bruce Hurst, Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd and Roger Clemens while gaining a reputation as a strong defensive catcher and a perennial American League All-Star. Gedman was behind the plate during the Red Sox championship drive against the California Angels and the New York Mets taking his share of the controversial blame for the 1986 Game 6 World Series disaster that is now part of Red Sox lore.

A free agent heading into the 1987 season, Gedman went unsigned during an offseason in which baseball owners were later found to have colluded against potential free agents in an attempt to take a stand against escalating player salaries. Gedman was eventually forced to return to the Red Sox but unable to rejoin the team until May due to the Collective Bargaining Agreement. With a late start most likely contributing to Gedman’s inability to find his swing and then an unfortunate ligament tear in his left thumb in late July, the 1987 season proved to be Gedman’s worst offensive year statistically. While continuing to work hard in an effort to find his way out of what had become an ongoing slump, the team eventually decided that Gedman was lost offensively, cutting ties with the former All-Star and turning catching duties over to Rick Cerone and later awarding the permanent job to Tony Pena.

Gedman bounced around after leaving the Red Sox playing for the Houston Astros and then the St. Louis Cardinals during the early 1990s. After being offered only minor league opportunities with the Oakland Athletics, New York Yankees, and Baltimore Orioles, Gedman opted to retire during the spring of 1994. He returned to the Red Sox organization as a minor league hitting instructor in 2011 and quickly worked his way through the Sox system eventually plateauing at the Triple-A level. After a decade as the organization’s Triple-A hitting coach, Gedman now serves as a player development hitting advisor for the Red Sox.

I caught up with Rich Gedman while he was still the hitting coach of the Triple-A Pawtucket Red Sox during the team’s final days at old McCoy Stadium in Rhode Island. Known for his blue collar approach and local Worcester ties, Gedman was happy to talk baseball in the home team dugout at McCoy, and was quick to reflect on what it was like to be the local kid who got to play for the Red Sox, the team he grew up rooting for.

“I was just a kid from a two-decker in Worcester, a house without a shower. We only had a bathtub,” said Gedman. “Since the day I was born I wanted to compete. I wanted to win. In the neighborhood, that could mean hitting more baskets, throwing the football farther, hit, catch, whatever. And you learned early that you wanted to make sure that you competed against kids who were better than you,” said the former Sox catcher. “It was one thing to win, but to get better you had to step it up a level.” The ability and willingness to compete against players who are considered to be better than you is something that Gedman believes is necessary for athletic success. “When you are from Massachusetts, they tell you that there are kids better than you from Texas, from California, and from Florida. But then when you see them you think, they look just like me, and you say to yourself, ‘I can play against these guys.’” We talked about youth sports and how important it is for kids to always “play up,” according to Gedman. “Everybody at this level was a shortstop and a pitcher in Little League,” said Gedman, making note of the fact that with each level a player is able to move up within an organization, the competition increases. “By the time you get here,” said Gedman looking out at the field, “every player on the field was the best kid on their team.”

Gedman shared the news of his first call-up to Boston with a smile. He was summoned into the manager’s office with Julio Valdez and some other prospects as the International League season was winding down at the end of the summer in 1980. “I got called into Joe Morgan’s office and was, like, ‘uh oh,’ because I had been called in there before,” said Gedman, his face turning more to a look of alarm. While able to foster a loose clubhouse atmosphere using the entire roster to win, Pawtucket manager Joe Morgan was more than willing to remind players that he was in charge. With that said, Gedman was shocked when he was greeted by Morgan happily relaying the news that he had been called up to the Red Sox. “Congratulations!” Morgan told Gedman. “You’d better get on I-95 because you’re going to Boston.”

It was an incredible, indescribable feeling to finally get called up to the Boston Red Sox. “I didn’t know what to do,” said Gedman. “My energy level went up. It’s just different playing at Fenway in front of 35,000 people than it is playing in Pawtucket. And me, being a local kid from Worcester, to be able to walk out into Fenway Park and play? I remember the first time walking up the runway to the field, the boards on the floor, rats running around, and the smell was just terrible. But then I walked up the stairs and saw the Green Monster and it’s just the most beautiful place in the world.”

Gedman found himself back with Pawtucket by the end of spring training in 1981, but it was not long before he was with the Red Sox again after an injury to catcher Gary Allenson. The Pawtucket Red Sox were in Virginia and they were just about to board a bus to Charlotte, North Carolina when Gedman was told that he had been called up to Boston. He was soon on a plane to Logan Airport. “The Sox sent a clubbie to pick me up at the airport. He parked the car right outside the terminal. When we came out the car was gone,” said Gedman. “I gave the clubbie the business, basically out of nerves, because I needed to get to Fenway. We asked a nearby state policeman about the car that had been parked in front of the terminal.” The policeman informed them that the car had been towed, but he also noticed that Gedman was toting an assortment of baseball bats. “The state policeman told me to get in his car and he drove me to Fenway Park personally,” said Gedman. “He kept in touch, calling years later to check in on me to see how I was doing.”

Gedman reflected on some of the differences with minor league baseball as it exists now as opposed to when he had played in Pawtucket as a young prospect. “Back then the minors were just about learning fundamentals. The serious adjustments were made in the major leagues. I learned things five years into the majors that kids are now learning in the minors,” said Gedman. “Part of that teaching is mental. The game has tells. You can see different things. Pitchers tip pitches. As a catcher you notice things other players might not, like a pitcher who sticks his tongue out every time he throws a fastball, or bites his lip when he throws a slider. And of course, if you notice it as a catcher,” said Gedman, “you can bet that eventually the hitters will pick it up.”

Gedman was excited about the upcoming move of the Pawtucket Red Sox to his hometown of Worcester even with the storied past of McCoy Stadium and the potential effect that the move would have on the Pawtucket community. “There is a lot of history here at McCoy. They do a lot of nice things here in Pawtucket, promotions and things that involve the community. But the good thing is, Massachusetts will finally get a brand new stadium. Baltimore, Texas, and Detroit all have state of the art, beautiful new stadiums in their downtown areas. There is a special history in Boston and it is obviously special at Fenway, but it will be great to have a brand new stadium in Massachusetts.”

I shared with Gedman something that I had watched him do during his playing days that I thought distinguished him from other catchers in the league. Whenever a ground ball was hit to the infield Gedman would always race along with the runner up the first base line to back up the first baseman in the event of an errant throw from a fielder. Although often instructed as the appropriate fundamental move for a catcher, I told Gedman that aside from watching him do it while catching for the Red Sox during the 1980s and also being someone who has watched a lot of baseball in my lifetime, I really couldn’t recall any other catcher doing this with the same fervor or frequency that he did. Gedman paused in thought and then said in the most humble manner, “Everybody does that.”

“It’s a blue collar game, a game in which you have to work hard. You have to go to work every day and it doesn’t always lead to immediate results, but playing this game means you have to keep showing up,” said Gedman. The former Red Sox catcher talked about the importance of work ethic, mental preparation, and the ability to make adjustments as examples of how to approach the game correctly, and how baseball is a more intellectual game than some of the other professional sports. “There is a game inside the game. Things are going on out there that aren’t necessarily happening while the ball is in play. There’s a lot to watch. You have to take it pitch by pitch. The game is much easier if you slow it down - this pitch, this inning, this game. If you don’t learn to do that, baseball is the hardest game on Earth.”

Gedman declared that our time had to come to an end, jokingly saying that if he didn’t get his butt into the manager’s office to prepare for that night’s game against Lehigh Valley he would be in serious trouble.

“Baseball has changed some, but it’s still the same game,” said Gedman, who then punctuated the moment with one last encouraging thought to which I couldn’t agree more: “It’s still a great game.”

If you like my articles, please hit the “LIKE” button. It will help to let me know that you are enjoying my writing.

I welcome and invite you to COMMENT.

And please SHARE these posts! This gives added support to my Substack page and also helps to add new readers.

Thanks so much to anyone who is reading Journeys with Jay!