Sebastian Belfanti is the Executive Director of the West End Museum in Boston. Located just across from the former site of the old Hotel Madison, demolished in 1982 after surviving as one of the final existing structures of Boston’s West End neighborhood, the location of the West End Museum is a sad reminder of Boston’s urban renewal project that became more about politics and misguided vision than progress and people.

I recently joined Belfanti on a walking tour covering many of the blocks that were so greatly affected decades ago, an area that could now benefit from recreating some of the neighborhood’s history as the city of Boston continues planning for its future. “The whole area,” explains Belfanti, “represents a history of people that were displaced.” Belfanti sees the West End as a story of continued change as much as it is one of architectural failure. As we stood across from the last remnants of the old Government Center parking garage, the concrete monstrosity completed during the 1970s that has blocked the downtown area from the old West End for nearly fifty years, Belfanti explained that the idea of redeveloping the West End was originally based on the principle of consistent architectural vision but became more dominated by government bureaucracy, greed, and politics rather than functional innovation.

After waves of immigration and the ensuing housing crisis of the 1940s, America’s cities were labeled as overcrowded and unappealing. Boston was seen as outdated and dirty. Decades before, when wealthy residents vacated Boston’s West End for new construction in what would become Boston’s Back Bay area, Irish immigrants who had experienced overcrowded conditions in other parts of the city began to take advantage of housing left available in the West End purchasing and subdividing buildings. The Irish who moved into the West End were soon joined by other immigrant groups including Italians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Greeks, Jews, Poles, Russians, and Albanians along with an African American community that was already living on the northern slope of Beacon Hill. The West End quickly became a lower middle class neighborhood that had a reputation for accepting anyone. “Women called down from small third-floor windows in languages I had never heard before,” according to former West End resident Richard Lourie in Howard Mansfield’s 1993 book, In the Memory House. “There were the smells of a dozen old countries in the hallways and the streets.” The West End was truly a convergence of cultures and quickly the most diverse neighborhood in Boston. “It was a neighborhood where visiting across race and ethnicity was common,” says Belfanti, “unusually accepting of people who would otherwise be ostracized by society.” 80 percent of marriages in the Bowdoin Street area, Belfanti says, were mixed race. It was traditional practice for West End residents to congregate in one home for dinner, eating together regardless of ethnicity sharing cultural traditions with neighbors.

When Boston Mayor James Michael Curley was sentenced to five months in prison during the late 1940s, City Clerk John Hynes was handed the job of interim mayor at Curley’s request. Curley was concerned about political competition. Mayor Curley promised Hynes lifetime tenure for the position he held as Boston City Clerk if he agreed to successfully watch over the city in his absence. In an effort to potentially eliminate a future opponent, Curley made Hynes promise that he would never actually run for mayor. When Curley returned from prison he proceeded to publicly insult Hynes for his lack of production during the time Curley spent in jail. Hynes abruptly decided to break his promise and run against Curley in the next election. To win, Hynes would need the votes of young soldiers returning from World War II as well as the votes of any eligible college students. In an effort to help gain Boston’s youth vote, Hynes employed 21 year-old lawyer and recent Harvard graduate, Jerome Rappaport. Rappaport devised a plan that helped Hynes unseat Curley and become the new Mayor of Boston. Hynes awarded Rappaport the position of Special Assistant to the Mayor despite his limited political experience. Hynes made it his mission to “redeem Boston in the eyes of America,” said former Boston Mayor and Governor, Maurice Tobin, who was serving as Secretary of Labor at the time. In an effort to build a new Boston, Rappaport and Hynes banded together to reimagine the city, reintegrating the voices of local business leaders back into City Hall, even going so far as to rewrite law codes to allow for new construction. Rappaport was told to select neighborhoods that might be expendable, areas that could be used to showcase the new Boston that Hynes was envisioning. East Boston, the North End, Charlestown, and the West End were originally chosen for demolition, according to Befanti. It was important to Hynes, however, that any area chosen for redevelopment would be central and visible. As a result, East Boston was dropped from the list. Charlestown was spared for the same reason. The North End, it was decided, was too isolated and removed from consideration. But the West End’s location in the center of the city made it an area that would be perfect for redevelopment, a brand new neighborhood that would help to symbolize the modern new Boston. “Boston’s citizens were told that nothing less than the city’s future was at stake,” Mansfield states in his book from a 1950s report by the Boston Globe. “If the West End can be switched from dilapidation to delight, it may be the trail-blazing spark which could revitalize Boston.”

Initial demolition efforts began in 1953. “The Boston Housing Authority labeled the West End neighborhood “detrimental to the safety, health, morals, and welfare of its inhabitants,” Mansfield writes. The city was quick to report, “the lots are too small, the streets are too narrow and crooked, the whole layout is out of date.” Mansfield’s book documents the city’s perception, designating the West End as “a den of the ten plagues - among them rats, vermin, tuberculosis, and juvenile delinquency.” City Hall worked hard to justify destroying all of the West End’s 54 acres, much of which consisted of federalist buildings designed by Charles Bulfinch. “The tenement buildings were of significant architectural value,” says Belfanti. But the city continued to publicize that it was impossible to save the area without destroying it. People living in the West End were encouraged to stop maintaining their properties, the city claiming that all buildings would be demolished sooner than later. Boston orchestrated a plan to create horrid conditions to justify demolition. In 1957, street cleaning and garbage pick-up in the West End, which was normally conducted twice a week, was reduced to once a week by the city. By 1958, the city no longer cleaned the streets of the West End. Garbage pick-up was also discontinued. Half of the West End contracted tuberculosis during the 1950s, according to Belfanti. An area that was once one of the wealthiest in Boston was now being cornered into conditions of filth and disease. The city circulated reports that the West End was a dangerous neighborhood with high crime rates, a determination that the Boston Police Department would not support. Families who lived on narrow streets that now qualified as alleys due to creative new zoning restrictions were ordered to vacate their homes. The city systematically created a feeling of lost hope and fear among people of the West End posting warnings on doors notifying residents that forced evacuations were imminent.

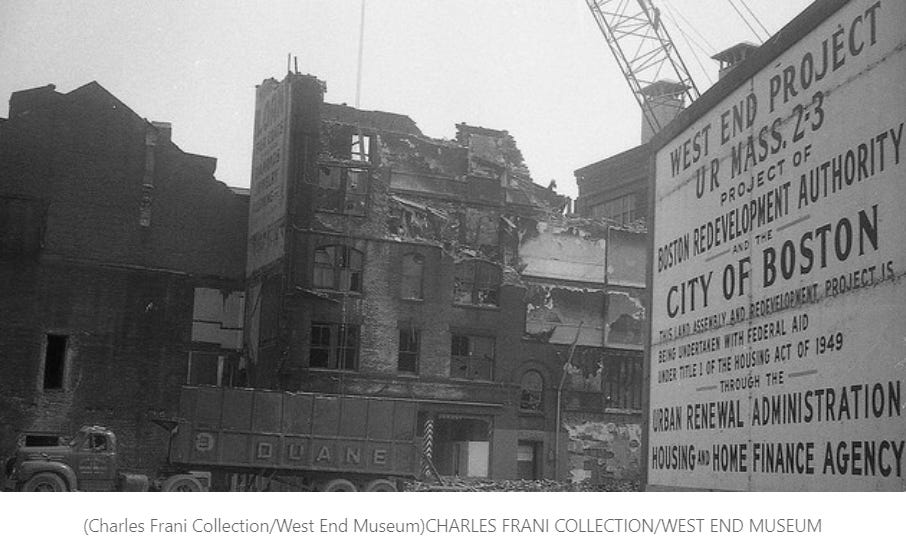

By the late 1950s, Jerome Rappaport had moved from his office at City Hall into the private sector as a real estate developer, but his attention never wavered from his redevelopment plans of the West End. To this point, West End residents had not been able to successfully mobilize against the city, still refusing to believe that an entire neighborhood could be taken away. But after nearly a decade of what appeared to be false promises by the city, rapid destruction of the West End began in 1958. In the Memory House documents the experience of Mary Foti Venditti, the daughter of Italian immigrants who grew up in the West End, was married in the West End, and lived in a home on Poplar Street in the West End along with her husband and children. “Comes the housing authority one day and tells us that we have to vacate our home, our property was being taken by eminent domain. We were confused and a little frightened. One day this fat man came to us with an offer which was far below assessment. How could they do this to us? We were paying taxes way above what they were offering. We refused the offer. How could anyone come into your home and take your property? In the meantime, Duane [the Wrecking Company] was leveling houses left and right. They wanted to get the job done as quickly as possible. We stuck to our guns. We refused to sign until we got a decent price. Duane would harass us. He would bang the wrecking ball against our house to scare us. Ours was about the last house left standing. We signed our home away. When the fat man came with the documents, he promised to find us a place to live. But that was a lie. A few days later he called and said the sheriff was in the house. When I got home, I found this fat man sitting down with a gun and an attack dog. Two men were taking our furniture. That was the summer of ‘59.”

5,000 West End residents were immediately affected by the city’s initial efforts with 7,000 still to be removed. Renters were offered $100 to vacate. Property owners were given only 40 cents for every dollar based on the value of their homes. Business owners got $2,500 if they agreed to pick up and move their establishment to a new location, but if a store closed its doors for good the owner received nothing, the city later claiming that it was unable to find former owners without a registered forwarding address. 6,300 West End residents were classified as lost by the city during this relocation. Data provided through studies from Harvard and M.I.T. indicated that despite claims being trumpeted by the city, the West End did not legally qualify for demolition. Finding its eventual way to City Hall, final efforts to save the West End from complete destruction went before the Boston City Council. The City Council voted to accept the findings of Harvard and M.I.T., determining that the city did not have slum clearance to justify destruction of the neighborhood. But it was too late. The paperwork for seizure had already been filed.

The housing crisis that originally inspired Boston’s redevelopment between 1944 and 1949 was no longer a problem by the time the demolition of the West End was complete. By 1960, so many people had left Boston for the suburbs that an effort was being made to bring people back. “The city’s leaders were desperate to lure suburbanites back to the city. In the 1950s the population of the suburbs outside Boston jumped 50 percent, and suburban employment increased 22 percent. Boston’s population shrank 13 percent, and its employment fell nearly 8 percent.” But Rappaport would not let go of his plan, believing that tall high-rises would be suitable replacements for what he saw as overcrowded neighborhoods. “We wanted a suburban feeling right downtown,” Rappaport said. “The important thing is that the area is cleaned of slums and middle-income apartments are provided that are taxable,” said Rappaport. “To attract the wealthy that had fled Boston,” said Rappaport years later in defense of his actions claiming he “tried to build a suburban oasis in an urban city.” According to Herbert J. Gans in a 1965 critique reinforcing the failures of urban renewal highlighted by Howard Mansfield, “The West End was chosen not because it was the worst slum, but because it was the best location for luxury housing.”

The eventual demolition of the West End included 51 streets, 800 residential buildings, and as many as 15,000 people. “Watching a house demolished - you knew the grandparents and the kids, knew the families, knew the kitchens - it’s like watching a person with cancer die,” Vincent LoPresti says in Mansfield’s book. “It’s hopeless, knowing there’s nothing you can do.” Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis confronted the issue two decades after the neighborhood was leveled with a message of intended healing. “We remember the old West End as one of the finest, most integrated and stable neighborhoods in America. And it was destroyed,” said Dukakis in 1986. “And as with all displaced, there remains the small hope of a homecoming.”

“Compared with the forgettable urban placelessness we often create today, the West End feels pretty good,” Boston Globe correspondent Robert Campbell reported in 2012. “Friendliness is what made the West End a neighborhood. And it was what people said they missed once they were relocated: no more dropping in, no more street corner chats and no more looking out for one another, no matter the ethnic group.” According to one former resident in Mansfield’s book, “The West End was warm with life on the streets and in the hallways.” Although numbers are now dwindling, people who were forced to move decades ago still consider themselves part of the West End community. Perhaps it is time for Boston to make the West End a major part of its current redevelopment efforts and begin to reverse the mistake made in destroying and displacing what could now be an economically, culturally, and historically thriving section of the city not to mention potentially creating an opportunity for the much deserved homecoming that former Governor Michael Dukakis alluded to.

While growing up in the West End, Joe Caruso remembers being in love with Fay Yaffa. “It was a one-sided affair. I never told her,” recalled Caruso years later. “She lived on McClean Street, and I’d walk up and down the street looking for dragons to conquer. But I think, in the end, I was in love with the West End, and the smell of hot bread wafting through the narrow, blessed streets.”