The W.H. Luddy and Son garage was the building that stood across the street from the Kingman house in the small town of East Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This garage provided the perfect backdrop for Wiffle ball, the activity that dominated so much of our summers as kids.

I first witnessed Eamon Kingman and his older brother Sean playing a game of fast-pitch Wiffle ball one spring morning more than four decades ago. I had never seen a Wiffle ball thrown so hard or with so much movement. Eamon and I were twelve years old at the time. Sean was nineteen. With five older brothers who had friends around the house much of the time, Eamon had learned to compete against older players, but not necessarily better players. Although younger and smaller, Eamon could do more than hold his own in this environment. With what I was witnessing that morning, I wasn’t sure if I could. I soon discovered that most Wiffle ball played at the Kingman house was of the slow-pitch variety with curve balls, screwballs, eephus pitches, and even a knuckleball that young Eamon had mastered that provided a challenge for even the best hitters. Whenever necessary, Eamon and I would ride our bikes up to Nate’s Hardware in the center of town to purchase as many Wiffle balls as we could either afford or were able to carry back. Old Nate, always suspicious of kids, would stare us down from behind the cash register that sat atop his antique wooden counter convinced that we were there to steal Wiffle balls rather than buy them. When we got back to his house, Eamon would take each Wiffle ball from its box and carefully apply a single layer of electrical tape around the seam to prevent it from splitting and also to add weight and stability to the ball. Standard yellow Wiffle ball bats were never tampered with. We looked with disfavor at kids around town who taped their bats which, to us, was similar to a Major League hitter using a corked bat.

The backstop was an old garage at the top of the Kingman driveway, an outbuilding that had been converted into a professional photography studio to support a family business some years before. The front was sided with barn board. Although no longer used for photography by this time, the studio’s interior was ornate with red carpet, tasteful paneling, and comfortable rolling chairs with light green upholstery similar to the kind that might be used on a 1970s talk show. With no windows and a permanently installed air conditioner, the studio was always dark and cool. The hotter the summer day, the more comfortable the studio seemed to be. For those of us playing Wiffle ball, the studio was like the clubhouse of a big league ballpark, a place to relax and regroup between at bats or to cool down while waiting to find out who your next opponent might be if you were playing in a tournament. The far corner of the studio had a small television set with the earliest version of an Atari game, and although I never had much of an interest in video games I watched many Space Invaders get destroyed at the hands of others who did.

A concrete ramp stood at the base of the studio, used for entry to the building when it had been an actual garage. A hard rubber regulation home plate was positioned a few feet in front of the studio’s ramp in the short, downhill facing driveway. The Kingman house stood at the corner of busy North Central Street and a sidestreet with minimal traffic called Dean Place. The W.H. Luddy and Son garage stood across from the Kingman driveway on the opposite side of Dean Place. The pitcher’s mound was on the other side of Dean, facing the Kingman’s driveway. The W.H. Luddy and Son garage on the opposite side of Dean Place rose behind the pitcher like the facade of an old baseball stadium, decorated in dark green and white like an old ballpark from the 1930s. Standing about thirty feet high at the center, the old bus garage dropped down more steeply to the left field side, while the right field part of the roof tapered off more gradually providing a generous area to use for a right handed hitter who wanted to drive the ball the other way. Luddy and Sons had three green garage doors big enough to fit a bus or a large truck through. The W.H. Luddy and Son sign was positioned above the garage doors with antiquated gooseneck-style spotlights mounted just below the sign. Both sides of the garage had large parking areas for the town’s fleet of Blue Bird school buses. The lot to the left was paved while the much larger parking area on the right field side of the garage was still dirt.

The ground rules were simple. Fair territory was marked by each side of the building. A ball hit to the left side that did not hit the garage either on the ground or in the air was a foul ball. The same was true for balls hit to the right. Any ball hit on the ground that reached the garage and bounced off of the building without first being touched by a fielder was a single. Any ball hit in the air over Dean Place that landed before being fielded was also a single. A ball hit off the garage at the level of its green doors was a double. A triple was any ball that hit the white wooden clapboard area above the garage doors. With the sloping design of the bus garage, hitting a triple was no easy task. A home run was a ball hit onto the roof, out of the park. In years to follow, a variation allowed fielders to race around the sides of the garage attempting to catch the ball as it rolled off the roof turning what appeared to be a home run into an out. This required both speed and knowledge of the surroundings, a task made even more difficult if the buses were parked on each side of the garage meaning you not only had to estimate where the ball might come rolling off the roof, but also had to navigate rows of buses knowing that as the ball came down it might also bounce along the tops of several school buses before it could be caught.

Games were played on most summer days depending on business at the garage. With Luddy’s open during the day the garage doors were often raised, meaning that more than a few Wiffle balls found their way into the service bays. When a ball went flying into the garage, it would be up to the discretion of both teams as to whether the ball crossed the designated line to be ruled a double. Sometimes a ball would have to be handed back to us by a mechanic, occasionally after landing in a pan of oil or a tray of transmission fluid. In such an event, the ball had to be set aside and was sometimes beyond the point of rescue. If there was no replacement ball, the game was either postponed or it was over. As we were frequently dealing with mechanics during day games in order to retrieve Wiffle balls, we were able to familiarize ourselves with their personalities. We learned which mechanics would be willing to help us with a ball and which ones would rather dump one of us into a vat of transmission fluid if their work had been disturbed by a ball. Earl Wood, a young mechanic who worked at Luddy’s one summer, lived at the Kingman house during the months of July and August that year and even played Wiffle ball with us on occasion, although usually while holding a beer and nursing a cigarette.

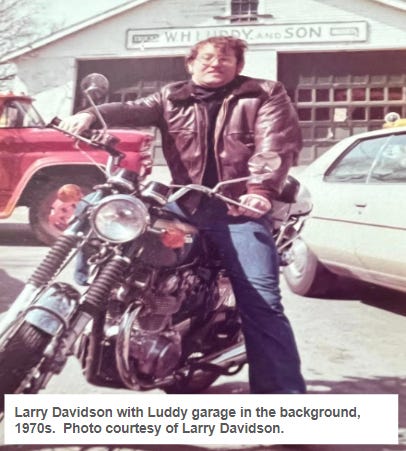

Summer days at the Kingman house were filled with activity. Local East Bridgewater Police Officers Tardie, Whiting, and Davidson frequently stopped in for a cup of coffee, catching up with the family at the dining room table. The oldest Kingman brothers, Billy and Patrick, would often be at the house with their wives, Allyn and Ann, along with all of their young kids. Gary Kingman would stop by in between shifts while working across town. Terry and Sean Kingman, still living at home, provided a constant presence for their younger brother Eamon and, subsequently, for me as well. Terry would never take a ride anywhere without bringing the two of us along with him in his Ford truck. Sean would always join us in any Wiffle ball contest and made a habit of hitting inside pitches well foul to the left side while the younger Eamon would athletically attempt to foil his efforts by hustling over to magically catch his mile high foul balls for outs. Wiffle ball games would come to a stop whenever Helen Harlow arrived in the driveway along with Eamon’s mother, Mitsi, in Helen’s red station wagon filled with groceries after a trip to the supermarket. Everyone at the Kingman house stopped whatever they were doing to help bring in bag after bag of groceries. At the time, I was of the belief that we were making a collective effort to help take care of Mitsi, but after listening to her reflect on those years during visits to see her shortly before she passed away in 2023, it became clear to me that Mitsi was the one who had always been taking care of us.

During summer nights the atmosphere tended to change with more cars in and around the driveway and more friends of the older Kingman brothers coming by the house. Wiffle ball games after dark would be played under the lights of the Luddy garage and sometimes an extra spotlight would be attached to the front of the studio shining down on the home plate area. Peter and Paul Doherty, brothers from across town, would often be there with their baby blue Ford Econoline van playing music from Billy Joel’s latest album, The Stranger, or they might have a James Taylor cassette playing from the van’s tape deck. Mark Eisenmann, a bit of a Wiffle ball legend due to a hustle play he once made suffering a significant injury after colliding with a dumpster in the process of chasing down a ball, was always a willing participant. Scott Harlow, the local high school kid who would later become a hockey star at Boston College and eventually go on to play in the NHL was always willing to grab a bat.

My first home run came during a Wiffle ball tournament on a hot August night. I managed to get my bat on one of Eamon’s normally unhittable knuckleballs and drive it deep into the darkness in left field. As former Red Sox infielder Lou Merloni recently said, reflecting on hitting his first Major League home run, “I didn’t have time to enjoy it at the time, but I remember every second of it now.” In reality, Eamon’s knuckleball was brutal. I remember one of the lights on the garage was right in my eyes at the point where the ball would leave Eamon’s hand. But the knuckleball had some hang time as it danced toward home plate. I regained sight of the ball with the black sky behind it and promptly drove it into the night. It wasn’t until the next summer, a full year later, that I discovered how to actually use my hands to hit and suddenly started taking Eamon deep with regularity. For Eamon, it was like the end of an era for a pitcher who had dominated me for so long realizing that I had finally uncovered the secret that he had never been willing to fully disclose to me, how to hit. From that point on, like Eamon, I became a legitimate opponent able to do more than just hold my own in that environment.

I recently returned to find the Luddy garage a shell of what it once was, no longer in business, quiet in comparison to the almost constant activity that once surrounded it. The W.H. Luddy and Son sign is now gone, and it has probably been years since the garage has harbored a single school bus. Across the street, some of the barn boards have fallen off the front of the Kingman’s studio, the siding in need of repair, the entry door on the side strangely a little forbidding although, to me, being there will always be synonymous with coming home.

As I positioned myself to take a picture of the old bus garage, a couple jumped out of a truck across the street and began walking their dog along the front of the building. Seeing that I was patiently waiting for them to reach the other side, the man yelled over, “Who are you? What are you doing?” I grew up here, I said. This is where we used to play Wiffle ball. In what sounded like an effort to verify my legitimacy he said, “Oh, then you must remember when it was Luddy’s, a bus garage.”

I remember, I said. I definitely remember.

I have driven by that building so many times in the past and didn’t know it was your mini Fenway Park! I remember you all playing baseball for EBHS and being very good. It all started with wiffle ball!

Great story, Jay! Brings back lots of memories of the Kingman’s and the EB crew!